August Spies

August Spies | |

|---|---|

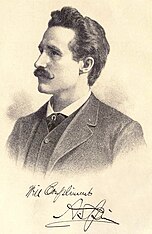

Spies' appearance at the time of his conviction in 1886 | |

| Born | August Vincent Theodore Spies December 10, 1855 |

| Died | November 11, 1887 (aged 31) |

| Cause of death | Execution by hanging |

| Resting place | Forest Home Cemetery |

| Monuments | Haymarket Martyrs' Monument |

| Occupation(s) | Upholsterer, newspaper editor |

| Political party | Socialist Labor Party |

| Criminal charges | Conspiracy to commit murder |

| Criminal penalty | Death |

| Spouse | Nina van Zandt (m. 1887) |

August Vincent Theodore Spies (/spiːs/, SPEES; December 10, 1855 – November 11, 1887) was an American upholsterer, radical labor activist, and newspaper editor. An anarchist, Spies was found guilty of conspiracy to commit murder following a bomb attack on police in an event remembered as the Haymarket affair. Spies was one of four who were executed in the aftermath of this event.

Background

[edit]Spies was born on December 10, 1855, in a ruined castle converted into a government building on the mountain Landeckerberg in the Electorate of Hesse, Germany.[1] His father was a government forestry official.[1]

Spies later recalled that he had a pleasant and privileged childhood, one filled with recreation and study.[2] He was educated by private tutors and trained for a career following in his father's footsteps as a government forester.[3] His father died suddenly in 1871, however, ending the comfortable financial situation for his mother, and August determined to set out for a new life in America, a country in which he already had a number of financially successful relatives.[4]

In Chicago

[edit]Spies settled in Chicago, where he became an upholsterer, involving himself in trade union activities. Due to the injustices he witnessed, Spies joined the Socialist Labour Party in 1877. He emerged as a leader of the SLP's radical faction; this faction provoked a split in the party by parading through the streets in military uniforms and shouldering muskets. After the English-speaking section of the SLP attempted to combine with the reformist Greenback Labor Party in 1880, Spies helped engineer a takeover of the party's executive committee and ousted the compromisers. When the national leadership of the SLP denounced the Chicago radicals and removed their newspaper the Arbeiter-Zeitung from its list of party organs, Spies led the formation of a revolutionary alternative to the SLP. In 1883, Spies was a leader in the Revolutionary Congress held in Pittsburgh that formally launched the International Working People's Association in America.

Spies had joined the staff of the Arbeiter-Zeitung in 1880, becoming editor in 1884.[5]

Haymarket Square

[edit]Speaking to a rally outside the McCormick Harvesting Machine Plant on May 3, 1886, Spies advised the striking workers to "hold together, to stand by their union, or they would not succeed."[6] Well-planned and coordinated, the general strike to this point had remained largely nonviolent. When the end-of-the-workday bell sounded, however, a group of workers surged to the gates to confront the strikebreakers. Despite calls by Spies for the workers to remain calm, gunfire erupted as police fired on the crowd. In the end, two McCormick workers were killed (although some newspaper accounts said there were six fatalities).[7] Spies would later testify, "I was very indignant. I knew from experience of the past that this butchering of people was done for the express purpose of defeating the eight-hour movement."[6]

The next day, May 4, Spies spoke at the Haymarket Square rally. Violence erupted and a bomb was thrown. The blast and ensuing gunfire resulted in the deaths of eight police officers and an unknown number of civilians. Seven men were arrested, including Spies. Later, Albert Parsons turned himself in.

Witnesses testified that none of the eight men charged threw the bomb. According to The Press on Trial, Spies had finished his speech but was still on stage when the bomb went off.[8] However, all eight were found guilty, and seven were sentenced to death. One, Oscar Neebe, was sentenced to 15 years in prison.

Trial

[edit]

Spies was put on trial for conspiracy in the murder of Officer Mathias Degan with seven other men. The defense initially sought to split the defendants into two groups. Spies was to stand trial with three others (Michael Schwab, Samuel Fielden and Oscar Neebe), separated from the "Monday Night Conspirators" (Louis Lingg, George Engel and Adolph Fischer), the more extreme defendants alleged to have attended a planning meeting in the Greif's Hall basement the night before the bombing. However, defense attorney William A. Foster shocked his colleagues and Spies by telling the judge the motion of severance musn't delay the trial and was merely perfunctory. Spies passed a note to another attorney that read, "What in the hell does Foster mean? I thought our motion was meant seriously."[10][11]

Albert Parsons would later turn himself in and all eight defendants were tried as a group. Spies would maintain his innocence and, despite the costly courtroom mistake, showed solidarity with his comrades through the trial, appeals, and at the gallows. Spies was one of three defendants, along with Lingg and Fischer, who were implicated in the possession of bombs. Spies testified he first obtained the dynamite out of curiosity. "I wanted to experiment with dynamite just the same as I would take a revolver and go out and practice." He kept the explosives on hand to impress reporters. "The reporters used to bother me a good deal, and they were always up for a sensation and when they came to the office I would show them these Giant cartridges... they would go away and write up some big sensational article." (Giant Powder was a brand of dynamite.)[12]

During the trial, the jury was allowed by the judge to consider as evidence articles written by the defendants in support of political violence, conversations about their desire for revolution, and other past materials. On the stand, Spies confirmed he had received an 1884 letter from Johann Most, an anarchist author of a how-to pamphlet on dynamite. Most's letter said he would proxy Spies 20 or 25 lbs. of "medicine", which prosecutors said was code for dynamite. In their appeal, the defense argued that police seized the letter from Spies' desk without a warrant, but the appellate judge said he could not pursue the matter because defense lawyers had not objected to the letter's admission during the trial.[13]

Gottfried Waller, a fellow anarchist, testified that at the meeting at Greif's Hall, two of the Monday Night Conspirators agreed that the code word "Ruhe" would be published in the Arbeiter-Zeitung to call anarchists to arms. The word appeared in the newspaper's "Letterbox" section on May 4, the day of the bombing. Theodore Fricke, the Arbeiter Zeitung's bookkeeper, testified that Ruhe was written in the hand of August Spies.[14] Malvern Thompson, a grocer, testified he observed Spies preparing for the Haymarket rally in Crane's Alley, where he heard Spies ask Michael Schwab, "Do you think one is enough, or hadn't we better go and get more?" and a reference to "pistols" and "police". Thompson said he heard Schwab tell Spies, "Now, if they come, we will give it to them."[15]

The photograph of the right bears an inscription: "To Mr. Jos. A. Labadie, with complements of Nina van Z.-Spies", on the back of the photograph Labadie noted that "[t]his picture was given me by her in 1887, before the death of Spies, on the occasion of dining with her and her father at their home in Chicago."

Thompson said the two were joined by a third man who Thompson later identified as Rudolph Schnaubelt, the lead suspect as the bomb thrower and Schwab's brother-in-law. Spies handed something to Schnaubelt, who stuffed it in his pocket, Thompson testified. Witness Harry Gilmer testified he saw Spies climb down from the wagon and light the fuse for the bomb thrown by Schnaubelt.[16]

At his sentencing, Spies denounced the police and prosecution witnesses. "There was no evidence produced by the State to show or even indicate that I had any knowledge of the man who threw the bomb, or that I myself had anything to do with the throwing of the missile, unless, of course, you weight the testimony of the accomplices of the State's Attorney and (Inspector John) Bonfield, the testimony of Thompson and Gilmer, by the price they were paid for it."[17]

Spies also charged that one witness, Gustav Legner, could prove his alibi but was threatened by police and paid to leave Chicago. Legner sued the Arbeiter-Zeitung for libel for repeating Spies' claim of bribery, denying he was told to leave town. Legner said he asked Spies before leaving the city if he should testify and was told he would not be needed. The Arbeiter-Zeitung agreed to print a retraction.[18]

In 1887, Spies and his co-defendants appealed to the Illinois Supreme Court (122 Ill. 1), then to the Supreme Court of the United States, where they were represented by John Randolph Tucker, Roger Atkinson Pryor, General Benjamin F. Butler and William P. Black. The U.S. Supreme Court denied the petition for certiorari (writ of error) by unanimous decision (123 U.S. 131).

In January 1887, while still in prison, Spies married Nina van Zandt (1862–1936). She was a graduate of Vassar College and the only child of a wealthy Chicago chemist. She published an article on the trial for the Chicago Knights of Labor. After Spies' death she married Stephen A. Malato, an attorney, in 1895. They divorced in 1902, and she reverted to the surname Spies. Nina Spies died on April 12, 1936.

Death and legacy

[edit]

Two of the defendants, Michael Schwab and Samuel Fielden, asked for clemency and their sentences were commuted to life in prison on November 10, 1887, by Governor Richard James Oglesby. They, together with Oscar Neebe, were pardoned and released on June 26, 1893, by John Peter Altgeld, the governor of Illinois.

Of the remaining five, Louis Lingg killed himself in his cell with a blasting cap concealed in a cigar on November 10, 1887. Spies, Albert Parsons, Adolph Fischer, and George Engel were hanged the next day, November 11, 1887.

As he faced his demise on the gallows, Spies shouted, "The day will come when our silence will be more powerful than the voices you strangle today."[19][a] The words are engraved on the Haymarket Martyrs' Monument in Forest Home Cemetery in Forest Park, Illinois, where Spies and the other Haymarket martyrs are buried.

May 1 was selected to celebrate International Workers' Day to commemorate the Haymarket affair.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Some sources report Spies' last words as "The day will come when our silence will be more powerful than the voices you are throttling today." This version is inscribed at the base of the Haymarket Martyrs' Monument.

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ a b August Spies, August Spies' Auto-Biography; His Speech in Court and General Notes. Chicago: Niña van Zandt, 1887; pg. 1.

- ^ Spies, August Spies' Auto-Biography, pg. 7.

- ^ Spies, August Spies' Auto-Biography, pp. 7-8.

- ^ Spies, August Spies' Auto-Biography, pg. 8.

- ^ Messer-Kruse, Timothy (2011). "The Investigation". The Trial of the Haymarket Anarchists. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-0-230-12077-8.

- ^ a b Green, Death in the Haymarket, pp. 162–173.

- ^ Avrich, The Haymarket Tragedy, p. 190.

- ^ Chiasson, Lloyd (1997). The Press on Trial: Crimes and Trials as Media Events. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-313-30022-6.

- ^ Chicago photographers, 1847 through 1900 : as listed in Chicago city directories. Chicago, Illinois: Chicago Historical Society Print Department. 1958. pp. 79, 89. Retrieved 11 January 2025.

- ^ Messer-Kruse, Timothy (2011). "Preparing for Trial". The Trial of the Haymarket Anarchists. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 41–44. ISBN 978-0-230-12077-8.

- ^ Avrich, The Haymarket Tragedy, pp. 263-64

- ^ Messer-Kruse. "The Defense". The Trial of the Haymarket Anarchists. pp. 95–96.

- ^ Messer-Kruse. "Road to the Supreme Court". The Trial of the Haymarket Anarchists. p. 145.

- ^ Messer-Kruse. "The Prosecution". The Trial of the Haymarket Anarchists. pp. 59–60.

- ^ Messer-Kruse. "The Prosecution". The Trial of the Haymarket Anarchists. pp. 72–73.

- ^ Messer-Kruse. "The Prosecution". The Trial of the Haymarket Anarchists. p. 74.

- ^ "The accused, the accusers: the famous speeches of the eight Chicago anarchists". Retrieved December 30, 2017.

- ^ Messer-Kruse. "The Elements of a Riot". The Trial of the Haymarket Anarchists. pp. 108–09.

- ^ Avrich, Paul (1984). The Haymarket Tragedy. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 393. ISBN 978-0-691-00600-0.

Works

[edit]- August Spies' Auto-Biography; His Speech in Court and General Notes. Chicago: Niña van Zandt, 1887.

- "Pages from an Editor's Sketchbook," Corvallis, OR: 1000 Flowers Publishing, 2012. —Excerpt from 1887 autobiography.

- The Accused the Accusers: The Famous Speeches of the Chicago Anarchists in Court: On October 7th, 8th, and 9th, 1886, Chicago, Illinois. Chicago: Socialistic Publishing Society, n.d. [1886].

Further reading

[edit]- August Spies, et al., Plaintiff vs. The People of the State of Illinois, Defendant: Error to the Criminal Court of Cook County: Abstract of Record. Volume 1 and Volume 2. Chicago: Barnard and Gunthorp, Law Printers, 1887.

- Bruce C. Nelson, Beyond the Martyrs: A Social History of Chicago's Anarchists, 1870–1900. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1988.

External links

[edit]- 1855 births

- 1887 deaths

- People from Hersfeld-Rotenburg

- People from the Electorate of Hesse

- Emigrants from the German Empire to the United States

- American anarchists

- Executed anarchists

- German anarchists

- People from Chicago

- Anarcho-communists

- Upholsterers

- Haymarket affair

- American people executed for murdering police officers

- German people convicted of murdering police officers

- People convicted of murder by Illinois

- People executed by Illinois by hanging

- Executed people from Hesse

- 19th-century executions of American people

- 19th-century executions by the United States

- Burials at Forest Home Cemetery, Chicago

- 1886 murders in the United States

- Trade unionists from Illinois

- Executed trade unionists